Tax Foundation has elected the Estonian tax system as the most competitive one among the OECD member states for six consecutive years – mainly due to its novel approach to corporate taxation. Instead of taxing the income generated by companies, the dividend distributed to the shareholders serves as the tax base for the Estonian cash flow tax which was introduced in 2000 in order to facilitate reinvestment of profits and support economic growth in a long run. The economic performance, business climate and international recognition in the last two decades proved the success of the Estonian tax reform. Is it conceivable that – similarly to Latvia – Hungary will follow Estonia’s example?

It might be surprising, but the concept of cash flow taxation is not entirely strange in Hungary. The tax base calculation method of the Small Business Tax (“Kisvállalati adó” or “KIVA” in Hungarian) introduced as of 1 January 2013 is similar to the tax base of the Estonian cash flow tax: payments to personnel increased by the approved dividend and the balance of capital transactions adjusted by certain other modifying items. According to the Hungarian tax authority:

“the calculation method of the tax base ensures that the profit devoted to expand the company’s assets does not increase its tax base, hence, KIVA is beneficial for enterprises of high growth rate. In addition, it is simpler conceptually than the regular corporate income tax.”

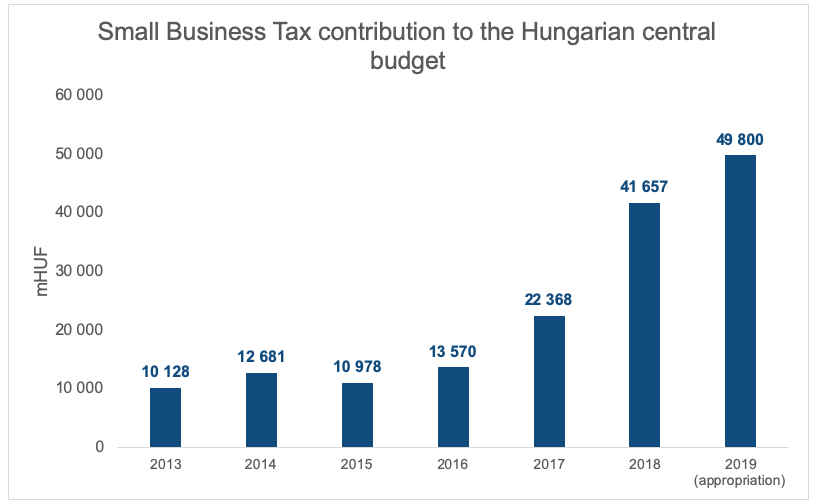

Although the popularity of the Small Business Tax was initially lacking behind the Small taxpayers’ itemized lump sum tax (“Kisadózó vállalkozások tételes adója” or “KATA” in Hungarian), KIVA’s contribution to the Hungarian central budget has shown a dynamic growth in the recent years.

Figure 1: Development of Small Business Tax revenue in the recent years (Source of data: Central Statistics Office)

Based on the data provided by the Central Statistics Office, it can be observed that the Small Business Tax revenue had been stagnating during the four-year-long period subsequent to its introduction, however, it has been increasing substantially since 2017. The main reasons behind the changing trend might be the following:

- The tax base calculation method of KIVA changed as of 1 January 2017, and

- The tax rate of 16% has been gradually decreased by the government (14% in 2017, 13% between 2018 and 2019, while 12% tax rate will be effective from 1 January 2020).

Due to the ease of administration, immediate recognition of investments in the tax base and relatively low tax rate, KIVA might be an attractive option to the taxpayers. However, only small businesses have been provided with the opportunity by the legislator to switch to cash flow taxation.

Even a report on cash flow taxation prepared by the EY upon a request of the European Commission mentions the Hungarian KIVA as an example of cash flow taxation. However, having regard on the fact that the report was disclosed in 2015, it could evaluate the performance of the Hungarian Small Business Tax (which had been introduced only two years earlier) in a very limited extent.

The optional nature of the KIVA and its limited availability (only small businesses are eligible to opt for it) make it even more difficult to compare with the corporate income tax which is the “default” tax for corporations in the country.

Even though it is unlikely that Hungary would replace its current corporate income tax regime in the near future, it is a positive move from the policy makers that they made possible for small businesses to opt for a taxpayer-friendly, low-admin cash flow taxation.

The writer is senior tax adviser at EY.