Reaching the same level of economic development as that of Austria has been a long-standing objective in the Central and Eastern European region, and thus in Hungary as well. The paper by the MNB's Chief Economist and Director presents on 5+1 charts how this can be achieved.

In the newly launched series of articles, the issue of convergence is shown in more details preserving this format, i.e. the 5+1 charts, by comparing the Hungarian figures with those of a relevant country or region. The first station of this series is Austria. The MNB's Growth Report, published today, which examines in a broader context how Hungary's sustainable convergence can be ensured, adds to the timeliness of the article.

Reaching the same level of economic development as that of Austria has been a long-standing objective in the Central and Eastern European region, and thus in Hungary as well. In evaluating the results, it should be taken into consideration that reaching Austria’s living standards is definitely an ambitious but realisable objective, subject to an appropriate competitiveness reform policy. The Austrian economy’s development level is outstanding by European Union standards: in 2017 its gross domestic product per capita adjusted for purchasing power parity amounted to 127 percent of the EU average, based on which Austria is the 6th most developed economy of the Community. By contrast, in 2017 Hungary stood at around 69 percent of the EU average, which is a major progress compared to previous years, but it still lags significantly behind Austria’s development level.

Convergence, therefore, has not materialised yet, but in the past years there was a clear improvement. In previous decades, several attempts were made to realise convergence; however, the road to sustainable convergence opened only after the measures taken in recent years. In Hungary, after 2010 several reforms fostered the raising of employment, improvement in the fiscal balance, decrease in external debt and through those, economic growth and the subsistence of families. In this paper, we present on 5+1 charts how the reforms helped Hungary come closer to the Austrian level in these areas (and in certain cases even surpass it). These results, by creating economic balance and growth, provide a proper basis for a turn in competitiveness, and thus Hungary may approach Austria also in terms of living standards.

Following the global economic crisis, Hungary has embarked on a successful convergence path.

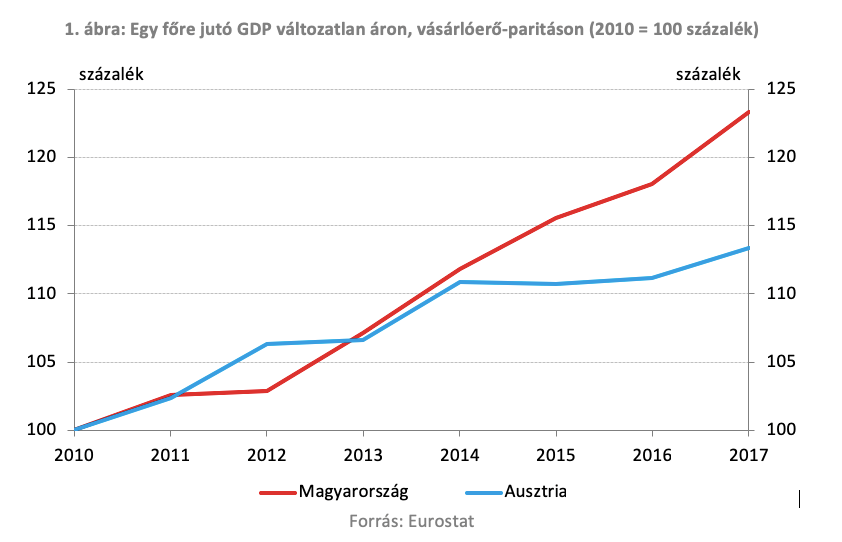

Gross domestic product is not only continuously rising since 2013, but the growth rate also exceeded the dynamics of Austria and the EU average in each year. Hungary’s cumulated real growth, calculated at 2010 prices, was 17 percent in the period under review, while Austria’s GDP rose by a total of 10 percent in the same period. Since 2013, the growth dynamics of the Hungarian economy, following the stability created by the fiscal and monetary turn, has been roughly twice as high as the EU average and Austria's growth rate. Raising employment, a cornerstone of growth, was essential for achieving the GDP growth necessary for convergence.

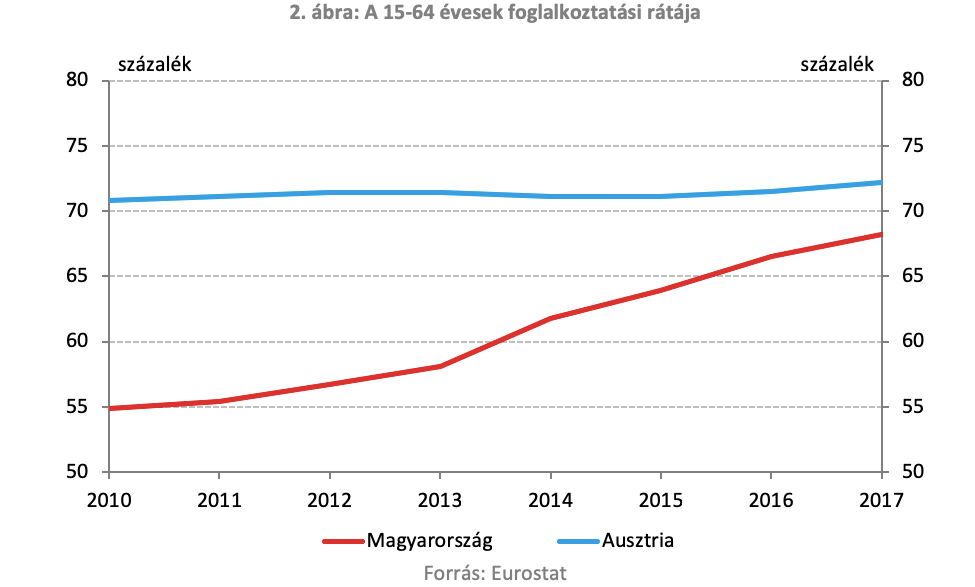

The Hungarian employment rate used to be among the worst ones in the EU; however, by now it exceeds the EU average and approximates the Austrian level.

The Hungarian employment rate was less than 55 percent of the total working-age population in 2010, which ranked Hungary the last in the European Union. The reform of the tax system and the tightening of social transfers managed to reverse this unsustainable situation in a favourable direction. As a result of the reforms, in 2017 the Hungarian employment rate already exceeded 68 percent, accompanied by a historically low unemployment rate of around 4 percent. Thus the Hungarian employment rate already exceeded the EU average and came close to Austria's 72 percent.

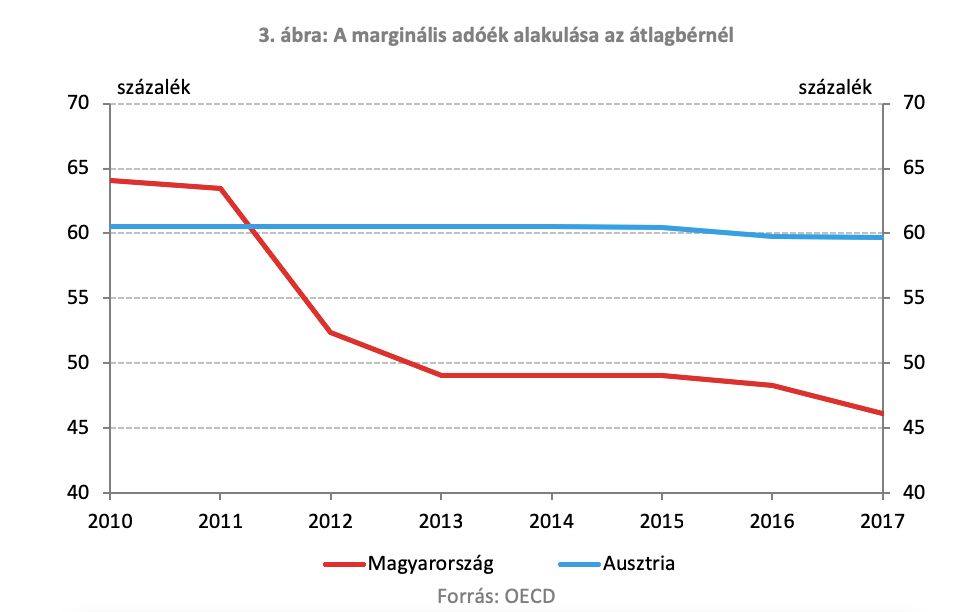

The substantial expansion of employment was essentially the result of the reduction in labour taxes.

In the case of the average wage, the marginal tax wedge, expressing the tax burden on one unit of extra income, was around 65 percent before the reform of the income tax system, which not only penalised extra work, but also hindered investment in human capital. The introduction of the flat rate income tax and targeted allowances replacing the tax credit available based on subjective right, all served the purpose of reducing the tax burden on labour and making it worth working more. The newly introduced targeted tax allowances were typically tied to labour market status (Job Protection Action Plan) and to parenthood (family tax allowance). The Job Protection Action Plan fostered the employment of the most disadvantaged groups in the labour market, while the family tax allowance aimed at improving the demographic situation by supporting families.

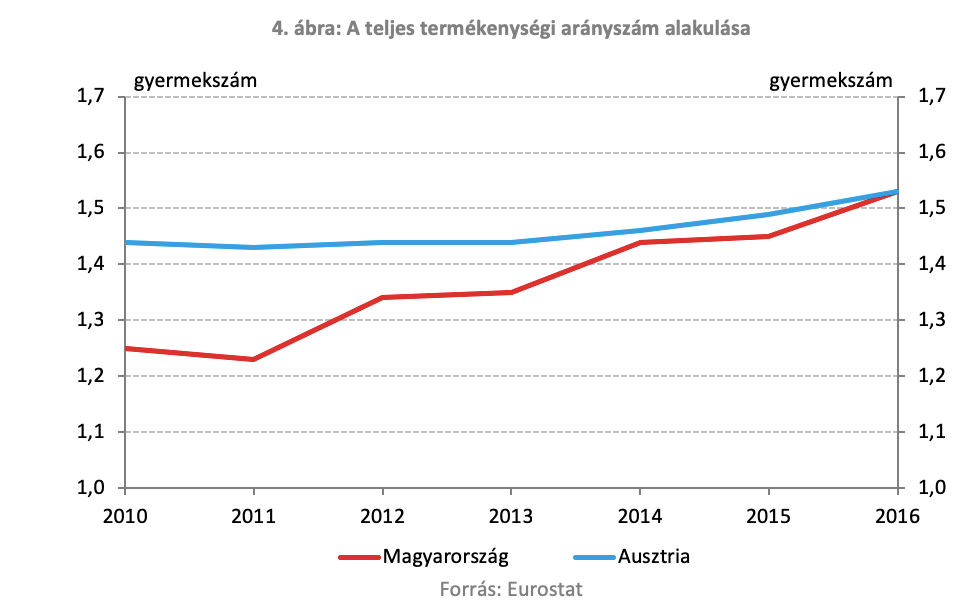

In the past years, several measures were taken to improve demographic trends, the results of which are already visible. Fostering parenthood is key among the family policy measures. It should be also borne in mind that raising the fertility rate helps mitigate or even stop the anticipated fall in the working-age population in the longer run. The rise in the total fertility rate, measuring the number of children per woman in child-bearing age, was the second largest in Hungary within the EU since 2010, by 2017 already exceeding 1.5, which essentially corresponds to the Austrian level, but falls short of 2.1, i.e. the rate necessary for natural social reproduction.

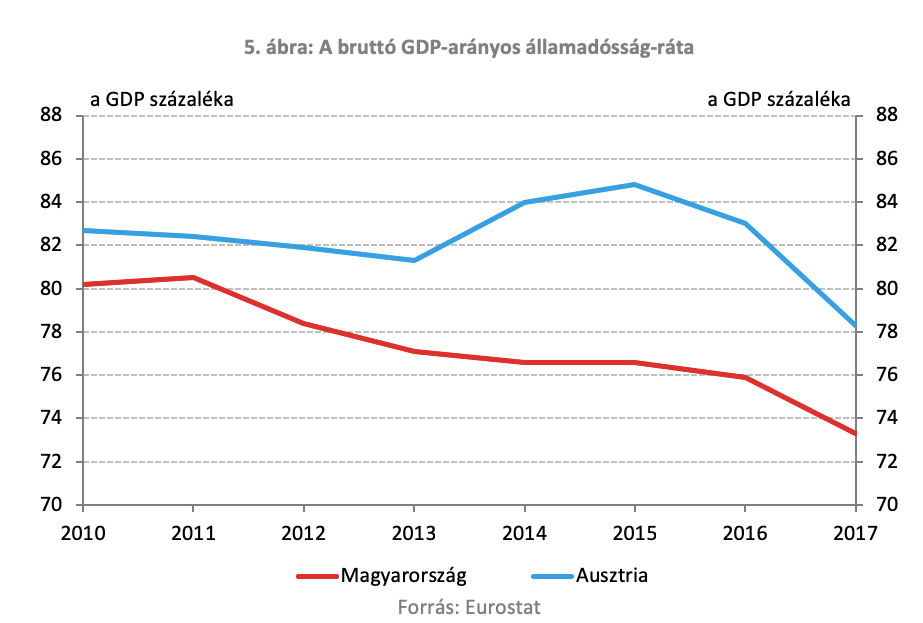

Sustainable growth and fiscal stabilisation contributed to the gradual decline in Hungary's government debt, thereby mitigating Hungary's vulnerability. In 2010, the Hungarian debt-to-GDP ratio, at over 80 percent, exceeded the EU average and it was also close to the level of Austria's government debt. As a result of the decline recorded in the past years, the Hungarian government debt fell to 73 percent, more strongly than that in the EU average and Austria's debt. The persistent decrease in debt is of key importance in terms of accumulating fiscal reserves, since in times of shocks, e.g. a crisis, the high debt ratio carries funding risks, which was clearly evidenced also by the financial crisis ten years ago.

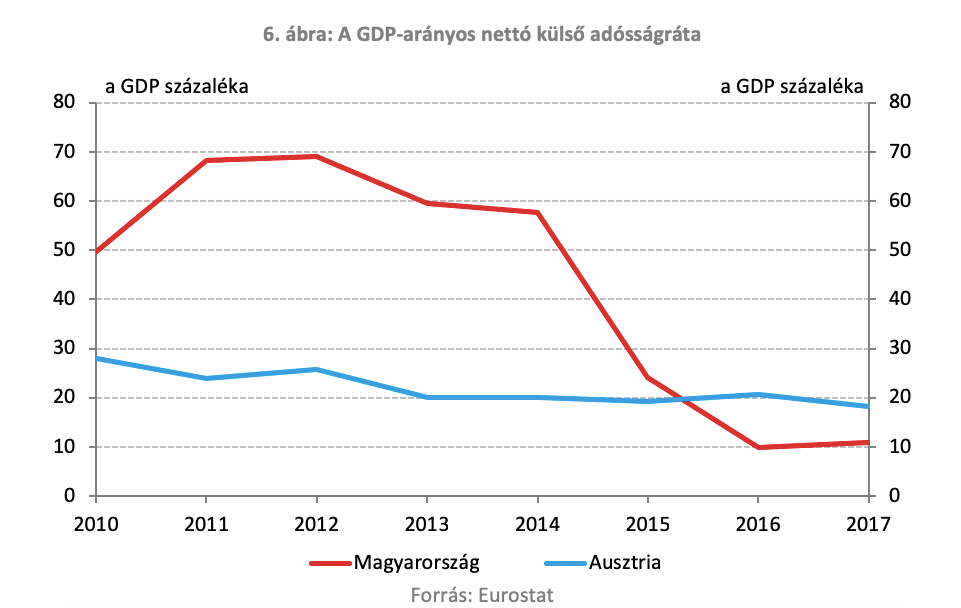

Another important indicator of financial vulnerability is the net external debt-to-GDP ratio, which declined in Hungary to an even larger degree.

As regards external debt, Hungary was one of the EU Member States that achieved the largest improvement since 2010, and by 2017 the Hungarian debt level was already below that of Austria. In recent years, net external debt declined by almost 60 percentage points as result of the repayment of debt liabilities and robust growth in nominal GDP. The decline in external debt and keeping it on a sustainably low level have reduced Hungary's external vulnerability and its dependency on external liabilities. According to the MNB's forecast, by 2020 Hungary's status may change from net borrower to net lender towards the rest of the world, subject to maintaining Hungary's persistently high net lending position.