The nature of inflation - time to rethink our measuring systems

EnglishFor almost a decade and in spite of significant efforts, central banks of developed countries have been unable to reach their inflation targets. The reason behind this phenomenon is the presence of two serious challenges. One of them is the need to understand the forces that drive the inflation trends of our age. We need to know how these factors changed compared to previous decades. On the other hand, at the start of the digital transformation, it is inevitable to ask ourselves whether our present systems allow us to properly assess the movements in our economies, as well as in inflation. It is only the deep analysis of these two problems and the right answers to them that will allow the decision-makers of the 21st century to pursue an efficient monetary policy again.

Since the last global crisis of 2008/2009, the general thinking about world economy has basically changed. One of the key lessons is that we do not believe in the self-regulating nature of markets any longer; instead, the stronger involvement of the state has been widely accepted. The analysis of issues related to income distribution has become more important, and the human factor is not seen as a rigid individual that makes rational decisions under any circumstances. However, in many respects, we still do not fully understand the world that is becoming more and more complex. One of these issues is the inflation of our age.

In spite of the interest rate environment in which rates are close to zero or actually getting negative, and in spite of the huge asset purchase programmes of large central banks, global inflation is still low. Central banks of the developed world have been trying in vain to reach their inflation targets for almost a decade.

- One of the reasons of missing the inflation targets is that the inflationary effect of previously determining economic principles has decreased significantly. In the meantime, structural factors and new megatrends, such as the effects of digitalization have become more and more important in the development of the inflation.

- At the same time, the bias in the measuring of the consumer price index - and usually the GDP - is becoming stronger in the digital age, and if it is not addressed, it may become a factor that influences the economic policy. The improved quality of the products, their shorter life-cycles, the increased ratio of services, the emergence of platform economies and the spread of free contents all contribute to the fact that the statistical framework established in the middle of the last century may measure the actual consumer inflation in a less and less accurate way.

Inflation, what we see now

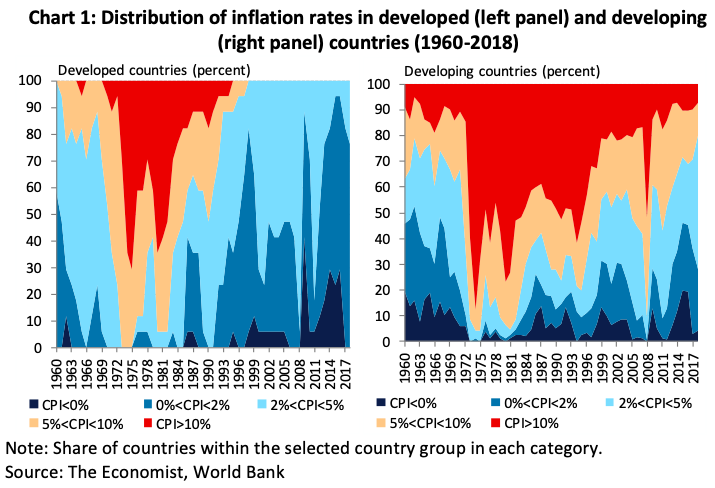

In the period following the crisis, global inflation dropped significantly. The moderate recovery of the world economy and the decreasing raw material prices both had the effect of lowering inflation rates. Although - in line with the increase in raw material prices - global inflation started to increase at the end of 2016, it is still below the central bank targets in developed economies. The increase in consumer prices was moderate not only in developed countries, but the phenomenon of missing inflation was observed more and more clearly in emerging countries, too (Chart 1). In two thirds of the countries following the inflation target, the increase in consumer prices still does not reach the desired target value. These countries produce more than 60 per cent of the GDP of the world.

And all this happens in a period when the large central banks of the world have been keeping their interest rates around zero or even in a negative range for a decade, and, in the meantime, as the grandest experiment in economic history, they have been trying to stimulate their economies with further asset purchase programmes. The trio of interest rates around zero, chronically low inflation and economic growth in developed economies that has been moderate for a long time has become the greatest challenge for economists and economic policy makers.

Why is it not possible to raise inflation close to central bank targets in the developed world?

There are three key factors behind this failure. On the one hand, since the global financial crisis of 2008/2009, the inflationary effect of factors that were previously considered critical has become significantly smaller. Economic thinking was determined by different prevailing concepts in each period, therefore the explanations regarding the development of consumer prices were dominated by different factors, too. Since the '50s, inflation processes were mainly identified as monetary phenomena. According to the monetarist theory (Friedman, 1963), the rate of the inflation is determined by the volume of money circulating in the economy. Since the '70s, cyclical factors came more and more to the forefront in the explanations of inflation (e.g. unemployment rate, output gap), and later they were extended with the incorporation of inflation expectations. With some fine-tuning, these theories determined the way of thinking about inflation right until the crisis. It is important to emphasize that the present inflation target following systems were created in that period, i.e. that was the theoretical framework that served as the basis of the decisions of the central banks.

In the period following the crisis, first we had to face the fact that economic recession did not go hand in hand with a significant drop in price level (deflation), and then we saw that the subsequent recovery and the stronger labour market were not coupled with faster inflation, either. The so-called Phillips curve became flatter and flatter.

In addition, we saw serious changes in explanations that were particularly important in small and open economies. The relation between exchange rates and inflation also got weaker, the rate of exchange rate pass-through dropped in both developed and developing countries. Although wages have started to increase recently in developing economies, this had a much weaker inflationary effect than we experienced before.

In the catching-up economies, the so-called Balassa-Samuelson Effect (inflation surplus originating from the productivity difference between exporting sectors and sectors producing for the domestic market) was another important factor that explained the development of inflation. Today, however, empiric observations suggest that this relation has also lost a lot of its explanatory power.

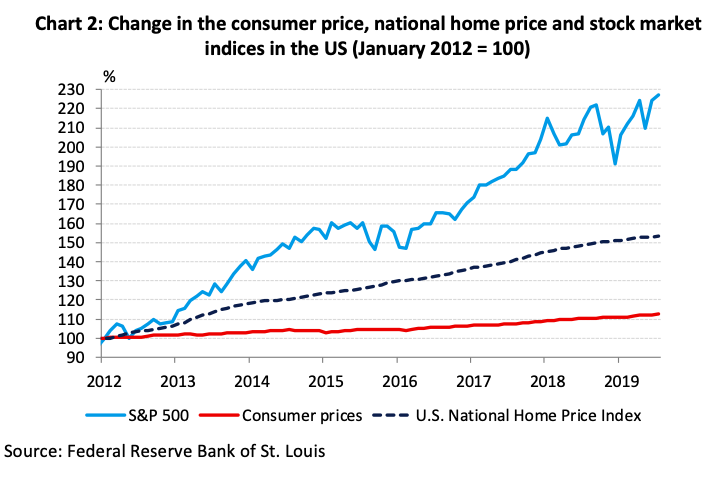

Another key reason why central bank objectives were missed in developed economies is that the central bank stimulus and the excess liquidity were not felt in the same way in each segment of the economy. Instead of influencing the real economy, excess liquidity resulted in higher financial asset and housing prices. The present share market rally has a stronger than ever relation with the direction of the monetary policy and the asset purchase programmes of big central banks. While the effect of monetary policy on consumption or investments was hardly noticed, key share indexes react to decision-makers' speeches and monetary policy information with great sensitivity. Instead of consumer inflation, we can witness a financial asset and housing price inflation. Chart 2 shows data regarding the United States. A similar phenomenon can be seen in most regions of the world.

The third factor is that structural effects that were managed outside the scope of monetary policy before, as well as emerging new or accelerating earlier megatrends also facilitate a reduction in inflation. We have seen it since the 1990s that companies transfer more and more of their production activities to countries with lower costs. With the widening of globalization, the prices were less and less determined by the prosperity of the given country. With the spread of global value chains, the level of inflation got more harmonized in the affected economies, while its level also dropped significantly.

The third factor is that structural effects that were managed outside the scope of monetary policy before, as well as emerging new or accelerating earlier megatrends also facilitate a reduction in inflation. We have seen it since the 1990s that companies transfer more and more of their production activities to countries with lower costs. With the widening of globalization, the prices were less and less determined by the prosperity of the given country. With the spread of global value chains, the level of inflation got more harmonized in the affected economies, while its level also dropped significantly.

Japan's example drew our attention to the examination of the relations between demography and macroeconomic phenomena, too. The changes in the demographic situation and the ageing of societies have a serious impact on consumer prices, too. A number of analyses indicate that the demographic transformation seen in the developed world may generate a permanently lower inflation.

In addition, the debts of the world are at historically high level. The high level of debts may reduce both consumption and investment willingness, while the level of public debt may give smaller ground in the future to a possible fiscal recovery.

And, last but not least, digitalization, automation and the new industrial revolution also have effects that facilitate lower prices. On the supply side, improved production efficiency and a significant drop in marginal costs causes lower inflation, while on the demand side, customers who are better and better informed in the virtual space trigger stronger competition, and thus a drop in commercial margins.

Consumer price index in the digital age: do we really measure what we perceive?

Digital development does not only transform the demand-supply relations in the economy, but it may bring the measuring of inflation - and economic performance in general - to a new level, too. This is badly needed.

The fifth industrial revolution will influence our lives more than ever before. At the moment, the consequences can hardly be quantified. As Raymund Kurzweil, the internationally recognized expert of the subject said: "We won't experience 100 years of progress in the 21st century - it will be more like 20 000 years of progress." (Kurzweil, 2001)

This process has already started. The calculation capacities of our machines are exponentially growing. Increasingly bigger slices of our economic transactions and social interactions are transferred to the virtual space, while, instead of owning physical objects, the real values will be experiences or access to a wide range of platforms. In fact, it happens more and more often that we pay with information and not with money.

The statistical systems created in the middle of the 20th century will be less and less able to depict a proper picture of this kind of world.

More and more analyses indicate that the official statistics may significantly overestimate the development of consumer prices. And in the present digitalization and technological revolution, this bias is getting more and more significant. In order to illustrate the problem, we mention a few specific reasons below:

- The consumer price index is calculated by the statistical offices on the basis of a representative consumer basket. However, this consumer basket is based on retail data collected two years ago. In a dynamic economic situation, where the life-cycle of products is dramatically shorter, two years mean a big delay. Think how much the digital devices used by us have changed in the past two years!

- The role of „ tie-in sale” keeps growing, i. e. digital devices have more and more functions, and they substitute former products. The cell phones in our pockets are already more than devices suitable for making phone calls or sending messages. A single device may serve as a camera, video camera, music player, map and related navigation. For these products and services, even one or two decades before, we paid separately, and today we get them together with the telephone.

- In the digital world, the use of free of charge services is more and more widespread. While in the old days we bought CD's, cassettes or vynil records, today we can simply download millions of songs for small amounts of money, or we might as well access them free of charge on a video sharing portal. The measuring and quantifying of these contents presents a serious challenge for the present statistical systems.

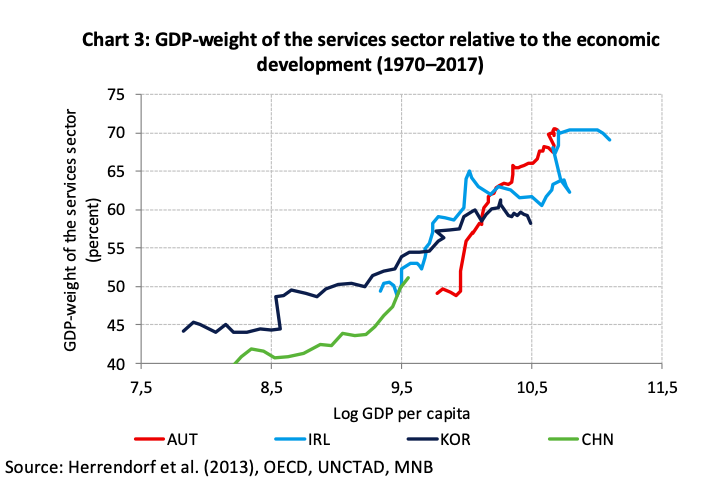

The increasing digital transformation, the globalization of services and the changes in consumer habits all work in the direction that the role of the service sector will be even more valuable in the 21st century. On the development track of economies, this is partly a natural process, in the proportion of the more advanced level (Chart 3), but the new technologies may effectively increase the volume of this. The measuring of the added value of services - unlike in the industrial sectors - is still a serious technical challenge, but the increasing complexity of the sector makes the situation even more difficult.

Inflation is still the sole anchor, but we have to rethink our measuring systems

This raises a legitimate question, i.e. what the central banks of the world can do in this situation. As to the factors that determine inflation, we can witness a paradigm shift. The increasing role of structural processes that influence inflation will direct the decision-makers in economic policy to new directions of thinking, and this may bring a change in the framework of economic policy, too.

In developed economies where the inflation target has not been achieved for a long time, it is necessary to rethink the inflation targets, and this may influence the level of the targets, as well as the monetary policy framework that is built on it. The natural level of the inflation in the digital age may basically differ from the standards determined in the 20th century.

Although the issue of giving more emphasis on housing or financial asset prices is raised by a number of parties, it is still important to preserve the primary role of the consumer price index as a monetary policy target variable. Increasing housing prices present an issue with serious social consequences, but in the lack of an extensive rental market, it is very difficult to get a clear picture about the price change of an asset in the case of which often 10-20 years pass between two transactions. It is good news in this respect that as a consequence of the global financial crisis of 2008/2009, central banks devote more and more resources to monitor the changes in the real estate market, so that, if necessary, they could react with their macroprudential instruments, independently of the monetary policy.

In addition to the deep analysis of factors that determine inflation and the rethinking of the monetary policy framework system, the reformation of the measuring of inflation is at least as important. Correct and properly timed economic policy decisions are based on the need to obtain the most accurate information on the operation of our economies. In connection with measuring, the technological development highlights new problems. It is our urgent task to adjust to these changes. Luckily, technology offers a helping hand to statisticians, too. It is entirely up to them how quickly they utilize the possibilities offered by huge databases and artificial intelligence. Those who react faster and with more courage, will be able to get a picture about the nature of the new forces that shape our world much sooner.